07 Temmuz 2020

A lawmaker’s faint heed for the realities of the past sparked a debate over female empowerment in Turkey. It also recalled the transformation of yesterday’s victims to today’s oppressors.

“Before the AKP government, there was even no concept of woman in Turkey.” (Ozlem Zengin)

Ozlem Zengin, a lawmaker from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), inadvertently stirred an impassioned debate over the role and place of women in the modern history of Turkey’s social fabric and political setting. She attributed the greatest contribution to her party in empowering women in a patriarchal society to uproot the male domination in politics, economy, and education. In her account, the current government placed the woman in higher social esteem in a revolutionary way by introducing rights never enacted before. But her feeble attachment to the course of realities in history only undermined her embellished narrative unmoored even from the basic facts of today’s Turkey.

After the demise of the Ottoman Empire, Republican Turkey found by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his companion after a war of independence at the end of the WWI saw a radical transformation of state and society. The top-down secularization and Westernization of the socio-political setting in all facets laid the groundwork for women’s elevation as social bonds of tradition had been shattered. To the knowledge of few, Turkey was one of the first countries in the civilized world that gave the suffrage and political representation to women. Turkey was again among the few Muslim countries where a female politician became a prime minister (Tansu Ciller in 1993). Sabiha Gokcen, the adopted daughter of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, became the first female combat pilot in the world in the 1930s. (This episode, though, was not without its downside given her role in an aerial campaign to crush an Alevi rebellion that later morphed into a massacre in 1937).

For all other unpromising elements associated with the painful experience of political modernity in Republican Turkey, the story of female empowerment was one of the sources of pride this country could legitimately enjoy. Against this set of facts, to claim that women had no rights whatsoever prior to the AKP government is to anchor in delusion and absurd denialism. This exactly what Zengin did without any qualm.

Many commentators, journalists and lawmakers chimed in after her flawed reconstruction of the history of feminist struggle in Turkey. Did women, as Zengin confidently claims, have no rights before the AKP government? Well, the sketchy survey I provided above reveals Zengin’s warped view of history and disproves her much-debated remark.

At the heart of public criticism that followed Zengin’s statement is her faint attention to facts. The second, and no less important, is the stark contrast between her rosy portrayal of women’s rights in today’s Turkey and the existing unpleasant reality given the far-reaching persecution of women after politically-driven witch-hunt and clampdown, something that slaps the careful observer in the face. (We are talking about the mass imprisonment of 17,000 women and more than 800 babies on ludicrous grounds). The metamorphosis of the very same people, who made their mark for fighting for the rights of the (pious) women but ended up being oppressors themselves, certainly merits a closer inspection in the context of Zengin’s inherent contradictions.

The Emergence of Ozlem Zengin’s Generation

During the heady days of 1997 and 1998, Bayezid Square in front of Istanbul University was a gathering point for thousands of students to protest a ban imposed by the National Security Council (MGK) to deny education to female students wearing headscarves. In the last day of February in 1997, the Turkish military issued a memorandum to the face of Necmettin Erbakan, the leader of Islamist Welfare (Refah) Party and Prime Minister in a Welfare-led center-right coalition government, at the MGK meeting that cobbled together the formidable generals and cabinet ministers to discuss matters of national importance. The infamous Feb. 28 signified a watershed moment in Turkey’s modern political history as it marked another (yet subtle) form of military interference in political affairs. A post-modern coup though it was, the MGK meeting led to the resignation of Erbakan and the collapse of the government in the months to come that same year.

The military interference, then the fourth in four decades, spawned a new era of repression against pious segments of society, sparking a new wave of purge, though not as chaotic and sweeping as the last one in the post-2016 era, in public service and the military. Perhaps above all, Feb. 28, which was rolled out as a series of government measures to eradicate political Islam from the political landscape and state institutions, was particularly designed to blunt the prospect of pious women’s incorporation into civil service and college education. It introduced a new set of rules to reorganize the entire education system to block conservative students’ access to higher education.

Consequently, tens of thousands of female students have unjustly been stripped of their constitutional right to education due to a simple dress code forced upon students almost at gunpoint (after the military memo). It remained in effect for more than a decade, albeit in decreasing forms. For headscarf-wearing women, it was a harrowing tragedy, with lifelong consequences.

The ban came to characterize the Jacobin implementation of laicism with no tolerance over the expression of people’s identity on matters deemed religious. Wearing a headscarf, for the majority of unflinching Kemalists, stood for the religiosity in a clash with the secular principles of the Republic. Their fixed treatment of the matter had deadlocked a smooth resolution of the ban for many decades. After keeping a low profile for more than a decade in power to avoid sudden unsettling of the political balance in the domestic realm, the AKP government finally terminated the ban through legislation in 2013.

Of all the traumatic events of the 1990s, the brazen mistreatment of Merve Kavakci, a hijab-wearing lawmaker, during the oath ceremony in the Turkish Parliament in 1999 became the illustrating embodiment of the suffering of women who wore a headscarf. She was the symbol of an era and of a generation. The mountain of grievances by conservative pious segments of society augmented the rise of today’s AKP.

Understandably, Zengin’s self-righteous position is driven by a sense of victimhood and the subsequent empowerment of the hijab-wearing women under the AKP administration. But the story of her generation had a dramatic turn that transformed yesterday’s victims to today’s oppressors in the course of a few years.

Politics of Memory and Tales of Victimhood

Aselites associated with the government party, which sprang from the ideological continuum represented by the Welfare Party line, commemorate the day (or month) every year with mixed feelings of triumph and tragedy, how to describe the legacy of the controversial Feb. 28 period implacably remains contested.

Political triumphalism had been the dominant mood among pro-AKP media folks when they set out to dwell upon the dark memories of the Feb. 28 until very recently. After all, the political underdogs, who were banished from democratic politics by the secular establishment (in cahoots with the military), now rule the county (since 2002). The vow to perpetuate the political regime designed by the architects of that military intervention for another 1,000 years spectacularly crumbled. (Five years after the post-modern coup, Erdogan-led AK Party came to power.)

The triumphalist tone has recently changed. Victimhood narrative tends to be reinforced with highlights from the era’s rights violations. It is this aspect of Feb. 28 remembrance that exposes a blatant normative contradiction in AKP Islamists’ approach to the 1997 post-modern coup.

The president and his supporters, however sincere they may be, forget one thing when they endlessly and tirelessly nurture the tales of victimization about the late 1990s. The Feb. 28 treatment of women, however troubling and repulsive it might have been, pales into insignificance in comparison to today’s treatment of 17,000 women and 800 plus babies at the hands of this same Muslim government. The oppressed victims of the Feb. 28 — Ozlem Zengin’s generation — inflict suffering on fellow sisters today far more than they themselves actually endured in that period.

Perfectly aware of that paradox and equally haunting dilemma, the AKP elites project their constant need of victimization into the tapestry of near-past teeming with crackdowns of varying forms and occasional suffering, while intentionally eschewing the moral reckoning of far more disastrous consequences of their contemporary policies today. Subscribing to an ever-recycling ritual of remembrance about the Feb. 28, therefore, provides a much-needed psychological escape to avoid facing the universally-known ramifications of the post-coup purge that Islamist AKP elites have created.

From Oppressed to Oppressors

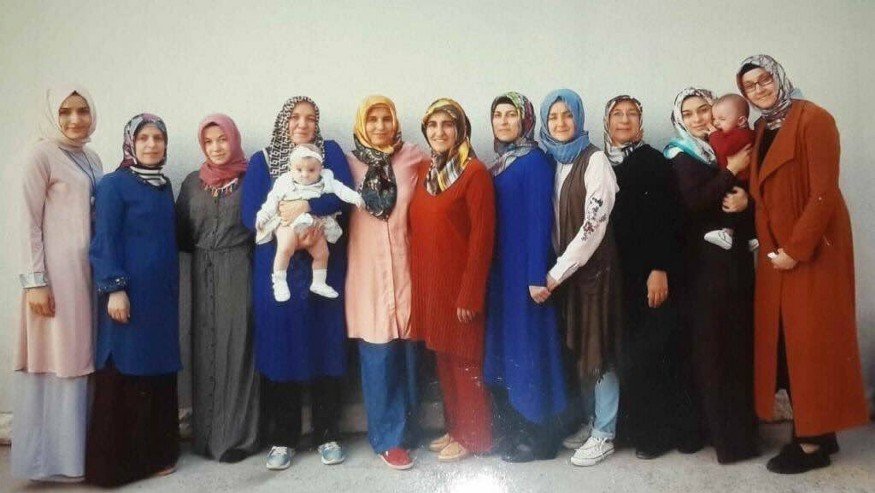

A picture of women from a prison in the western Turkish province of Bursa on Feb. 28, 2019.

This brings to the main argument of this essay. How did yesterday’s victims end up being today’s oppressors with no compassion for other suffering people?

Omer Faruk Gergerlioglu, a champion of human rights and a lawmaker from the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP), joined the debate, expressing his disappointment over this transformation.

“I fought for the restoration of rights of hijab-wearing women for my entire life,” he intoned last week. “But [I did not put myself in this fight] only to see hijab-wearing women [in the position of power] becoming oppressors themselves.”

Haluk Ozdalga, a former parliamentarian deputy from the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), exuded a similar sense of dismay at today’s glaring freedom violations by the government. In his response to Zengin, he did not mask his disappointment as well.

“I completely agree with Mr. Gergerlioglu. I, too, always stood against the headscarf ban, I tried to explain this to the Kemalist party of which I was a member and executive, it somehow didn’t work. But not for the establishment of an oppressive regime,” he tweeted.

The picture shared here is a sharp rebuttal of the AKP’s Feb. 28 narrative. As the government marked the 22nd anniversary of the coup last year, media was awash with stories of how pious women had deliberately been targeted by the Kemalist regime in the late 1990s. On the same day, the picture of a group of women from Bursa prison appeared on social media. There could not be a more telling contrast to illustrate the chasm between the narrative and deeds. And the picture is not about a distant past, but it was taken in the present (last year) under the same government.

Gergerlioglu offered a scathing indictment of Zengin and her party. The HDP lawmaker, who himself has a conservative background, lampooned the government for the exploitation of religion for political benefits. “No government has done more harm to religion than this AKP,” he implored, reminding the cascading examples of political persecution by the Islamist AKP government against its opponents, especially against fellow Muslims.

The president of Atheism Association today rejoices at the AKP policies. He says that “We don’t need to do anything to promote atheism. The AKP, on behalf of us, successfully does it.” Thanks to this government, there is an emerging antipathy towards religion, a growing social alienation from religious values. (Omer Faruk Gergerlioglu, HDP)

When a hijab-wearing judiciary member was recently appointed as a public prosecutor for the first time in the country’s history, it was hailed as the dawning of a new era and as a historical correction of the wrongs done in the past. But this did not generate any enthusiasm for many people in other quarters of society.

Some commentators failed to resist the temptation to remind the contradictions that subtly lie at the news itself. “A headscarf-wearing woman was appointed as a prosecutor (only to arrest and persecute other hijabi women),” one quipped on Twitter.

The obsession with seeing hijab-wearing women in positions of power fails to obscure the fact that these same people unabashedly countenance the government’s chokehold of Turkey’s democracy and the undoing of other freedoms. They see no scruples in being part of an anti-democratic crackdown on the political opponents of the government. They certainly see no ethical contradiction in their role to send pregnant women to prison on dubious legal grounds after politically-motivated trials.

The story of the prosecutor’s appointment, in this respect, is no mere empowerment of women. It is just broadening of the AKP-affiliated women’s achievement through the channels of nepotism and political favoritism. And the story fails to instill any joy for the larger segments of society as long as those newly-appointed public servants voluntarily embrace and even carry out all the brutalities of the apparatus they work for.

Yorumlar